"How should we judge Art?" An essay on Walton's Aesthetic Contextualism

The issue of how art is - and how it ought to be - judged is central to debates of the artworld. Kendall Walton attempts to end this debate with his notion of 'Aesthetic Contextualism'. How convincing is this account of artistic interpretation?

Introduction

In Categories of Art, Kendall Walton(1970) attempts to establish the superiority of Aesthetic Contextualism over Aesthetic Empiricism, via discussion of the importance of categories – and the existence of correct categories – by which to judge art. I argue that whilst there are a number of difficult edge-cases which he does not sufficiently counter, the majority of Walton’s argument is convincing and does indeed establish the superiority of Aesthetic Contextualism.

Note that in this essay, I take the purpose of any theory of appreciation as a means of communication and evaluation of art, between people and across time (“the artworld”)(1974:91). This is similar to Lopes(2014), who argues that “theories are informative in so far as they give us insight”(2014:125), both in terms of how people currently appreciate art, and how they ought to (be that in the ‘correct way’, or in allowing more effective communication and judgment of artworks). As a result, any judgement of the superiority of Aesthetic Empiricism or Contextualism will rest on the convincingness and extent of these insights.

1. Accounts of how people judge art

Before we can proceed to an analysis of Aesthetic Contextualism, we need to understand specifically the nature of Aesthetic Empiricism, as in many ways the former is a refutation of the latter.

First, Aesthetic Empiricists take the aesthetic (or “Gestalt”) (1970:338) properties of a work – elegant edges, sweeping and graceful brushstrokes, vibrant and lucid colouring, etc – to be emergent out of their non-aesthetic properties – mere physical features, such as smooth surfaces, 90-degree corners, or a mono-chromatic palette. Thus, any judgement made about a work ultimately refers to its aesthetic properties, though will still “depend on”(1970:337) its non-aesthetic features as a partial grounding.

However, Aesthetic Empiricists such as Sibley(1964), recognise that that “no combination of non-aesthetic properties ever suffices, logically, to guarantee presence of an aesthetic one”(1964:5). Instead, what else is needed for a viewer to make a judgement about a work is what the viewer adds: their own interpretation. Though tempered somewhat by a recognition that experience and expertise is needed – as Hume(1757) argues, the discrimination of “taste”(1757:23) – the scope of interpretations is essentially still at the viewer’s discretion. In this way, the same artwork can be judged oppositely, depending on the interpretation of the viewer, and so is necessarily subjective, placing no restrictions or truth-conditions on possible interpretations to be made by viewers.

Crucially, it is also only these factors which determine how a work is to be judged; “once produced…the work must stand or fall on its own…regardless of how it came to be”(1970:334). This means that the context in which an artwork was produced, the intention of the artist, etc, are all irrelevant considerations to the Aesthetic Empiricist, “any more than a contractor's intention to make a roof leakproof makes it so”(1970:336). The argument of the Aesthetic Empiricist is broadly convincing, since personal interpretation is important in how people ordinarily judge art (even if disregarding historical context is somewhat reductive, losing much of what makes the work unique).

Given this picture, Walton’s aim is to narrow the scope of interpretations, and provide a more holistic account of how people judge works. Central to Walton’s argument is that of ‘kind-sensitivity’(1970:346): works are not simply elegant, graceful, or daring, but are such relative to a given kind. As a description of how people currently judge art, this is extremely convincing; the use of timpani in a composition is completely ordinary if considered as orchestral work, but if intended for a string quartet, then instead as daring and shocking (even questioning whether it can belong to this category). In this way, people will very rarely consider any work to be absolutely daring or mundane, but recognise that degrees exist when comparing to other works of a similar kind.

Walton formalises his account of categories by sorting aesthetic properties into three groups: Standard, Variable, and Contra-standard. In order, these are features which “the lack of…would disqualify”, which has nothing to do with the works’ membership of a category, and “whose presence…disqualif[ies] works” to a category(1970:339).

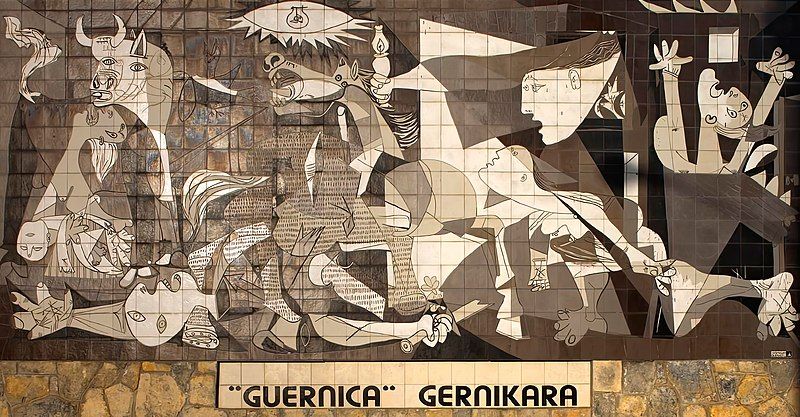

Elucidating this, Walton imagines two worlds – one in which Picasso’s Guernica is normally considered, and another, in which exists a category of art called ‘guernicas’, whose “colors and shapes [are] of Picasso’s…but the surfaces are molded to protrude from the wall like relief maps”(1970:347). In our world, Picasso’s Guernica is violent, dynamic, and disturbing, since the colours and shapes are variable properties, whereas the flatness of the painting is standard – yet in the other world the same work is cold, stark, and lifeless, since flatness is variable, and these colours and shapes standard. In this way, the standard features are common to all works in the group, so are accepted with little attention or scrutiny – whilst variable features are what distinguishes works within the category, providing different “aesthetic reaction[s]”(1970:347). As such, Walton views the context of both which category a work belongs to – as well as which features are variables, standard, or contra-standard – as necessary conditions for aesthetic appreciation, rather than merely what features the work has in isolation to others of a similar kind.

Again, as an explanation of how people already judge art, this ameliorates the position of Aesthetic Empiricism from mere ‘taste’; in suggesting any interpretation of a work is possible, much is lost regarding the origin of these judgements. People – when judging a painting – may see it as dynamic or bold, though these come under the context of expectations, which are derived from previous experience and comparison to other paintings of a similar kind (a point Hume almost makes regarding expertise)(Ransom, 2020:69). Thus, aesthetic judgements are never isolated – something that aesthetic empiricism is unable to adequately explain, as a theory of appreciation.

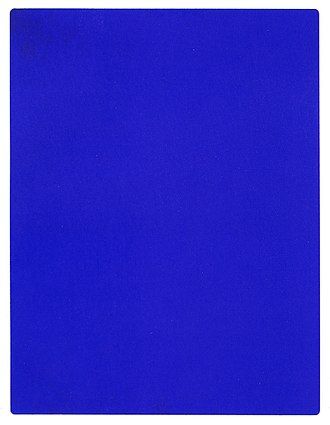

This said, Aesthetic Contextualism is not a perfect theory; avant-garde art, for instance, is made to contain contra-standard features which would remove them from consideration of a category. In this case, works by Yves Klein, for instance, should not be viewed as paintings at all, since their mono-colour is contra-standard to the category. Though Walton recognises that the “offending feature[s]”(1970:353) will eventually expand the definition and allow such works to be considered more commonplace, this doesn’t explain how appreciation in the period from conception to expansion is possible – something notably accounted for under the subjectivity of Aesthetic Empiricism.

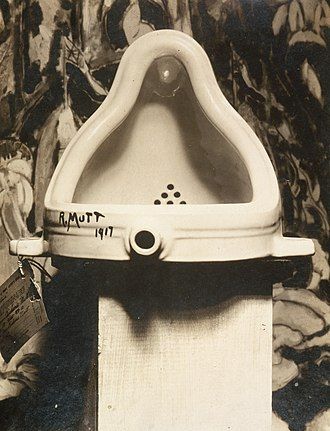

Nathan(1973) builds on this, taking the case of Schoenberg’s earliest 12-tonal works, which were certainly not accepted at the time, containing many contra-standard features – or further in Duchamp’s infamous Fountain(1973:541). In both these cases, Aesthetic Contextualism loses elements of the work, by the restrictive requirements for categorisation – limiting the scope of aesthetic appreciation. Furthermore, we can see that in such cases, until the artworld caught up, Aesthetic Empiricism would perhaps been the only way to fully make sense of the art presented.

This said, whilst these edge cases clearly provide some difficulty in the extreme cases of innovative art, in the majority of cases Aesthetic Contextualism is still clearly superior to Aesthetic Empiricism, in explaining how people judge art.

2. How people ought to judge art

However, as noted previously, the other purpose of a theory of aesthetic appreciation is to provide some insight into how we ought to judge art. For Aesthetic Empiricism, there are no direct prescriptions of how to judge art, since the principle is more to allow people the most freedom of interpretation in judging art, giving them a language of appreciation less constrained by correct or incorrect categories. In stark contrast, for Walton, there are express “correct way[s] of perceiving a work”(1970:357), leading to a singular correct category in which to view it. Specifically, there are four conditions for this category: the category with least contra-standard features, the category in which the work comes off best, the category which was “intended or expected” by the artist, and the category which was “well established in and recognised by” society at the time (1970:357).

However, immediately we see issues with this – what is to happen in the cases where the conditions contradict each other? Laetz(2010) notes that the categories in which a work comes off best is likely to be the one with least contra-standard features, yet clearly may not be the one which the artist intended(2010:294). If Picasso tripped and fell, spilling paint over a canvas, would we say that it is impossible to consider this as a work of an expressionist kind, rather than, as an artistic accident?

Walton here somewhat pre-empts this critique, convincingly arguing that whilst it is very convenient to find extraordinary categories in which the work comes off “as a masterpiece”(1970:360), it is still incorrect. In fact, erasing the artistic and historical contexts of such works, for Walton, would be like choosing to selectively translate a poem into a language it sounds best in, “even if this is a language which neither the poet nor anyone else has ever spoken or used”(1973:268). Since the history and intention behind the work are essentially linked with the piece, to choose to incorrectly interpret it is practically the same as to physically alter a painting to make it look better. This is convincing, since as with interpretation previously, context is central to understanding the work, now both as how people do, and how we should. It is also true that Walton does still argue that how the art comes across is more “likely”, but not necessary, when correctly perceiving it(1970:357).

A similar critique is mounted by Nathan, who argues that a work’s category being established in a society need not be relevant in determining the correct perception, if it is already how the work comes off best, and how the artist intended it to be interpreted(Nathan, 1973:540).

Whilst Walton himself does not counter this critique, Davies(2020) does – arguing in a similar manner that it is merely likely that the way the work comes off best is the category established in society at the time, since contra-standard features of a work are partially internalised by each “generation”(2020:79). Though inventive, this response is somewhat unsatisfactory, as it dismisses the point as unlikely, rather than providing a concrete reason why historical context is necessary for determining the correct category. Despite the vast majority of artworks’ congruence between their historical contexts and categories they come off best in, it is notable that Aesthetic Empiricism in this regard does not suffer the same restrictions, instead allowing the viewer a framework to appreciate art more freely (though coming with the philosophical baggage explained previously).

This said, Aesthetic Contextualism’s prescription of ‘correct categories’ is still mostly convincing – as context of the work remains central to understanding it – despite still falling prey to some minor counterpoints about the consistency of such insights in unusual cases (which are arguably more avant-garde works such as Fountain which we are concerned).

Conclusion:

In conclusion, whilst Aesthetic Empiricism retains some tempting advantages over Aesthetic Contextualism – including less restriction of interpretation and category-consideration – the latter’s insights into both how people judge art, and how they ought to, provides an overall superior theory of aesthetic appreciation. Specifically, discussions of kind-sensitivity and the properties of artworks give us a more accurate account of how people judge art than pure subjectivity – factoring expectations and comparisons to works of similar kinds.

Furthermore, in defending the ‘correct categories’ by which to judge art, Walton convincingly argues both the elimination of selective interpretations of works, as well as the importance of context beyond interpretation, into the artwork itself. Despite some challenging edge-cases, the vast majority of Walton’s explanation is highly convincing, and superior to aesthetic empiricism in providing fuller and more reliable insights.

Bibliography:

- Danto, Arthur: “The Transfiguration of the Commonplace” (1974) The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 33, No. 2 (1974).

- Davies, David: “’Categories of Art’ for Contextualists” (2020) from ‘Symposium: ‘Categories of Art at 50’’ in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Vol. 78 No.1 (2020).

- Dominic, Lopes: “Appreciative Kinds and Media” (2014) in Beyond Art (OUP, 2014).

- Hume, David: “Of the Standard of Taste” (1757) (The Birmingham Free Press, 2013).

- Laetz, Brian: “Kendall Walton’s ‘Categories of Art:’ A Critical Commentary” (2010), British Journal of Aesthetics, Vol. 50, No. 3 (2010).

- Nathan, Daniel: “Categories and Intentions” (1973) Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Vol. 31 (1973).

- Ransom, Madeleine: “Waltonian Perceptualism” (2020) from ‘Symposium: ‘Categories of Art at 50’’ in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Vol. 78 No.1 (2020).

- Sibley, Frank: “Aesthetic Concepts” (1964) The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 23, No. 2 (1964).

- Walton, Kendall: “Categories of Art” (1970) The Philosophical Review, July 1970, Vol. 79, No. 3 (1970).

- Walton, Kendall: “Categories and Intentions: A Reply” (1973) Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 32, No. 2 (1973).