Insights in Evil I: Arendt and the Banality of Evil

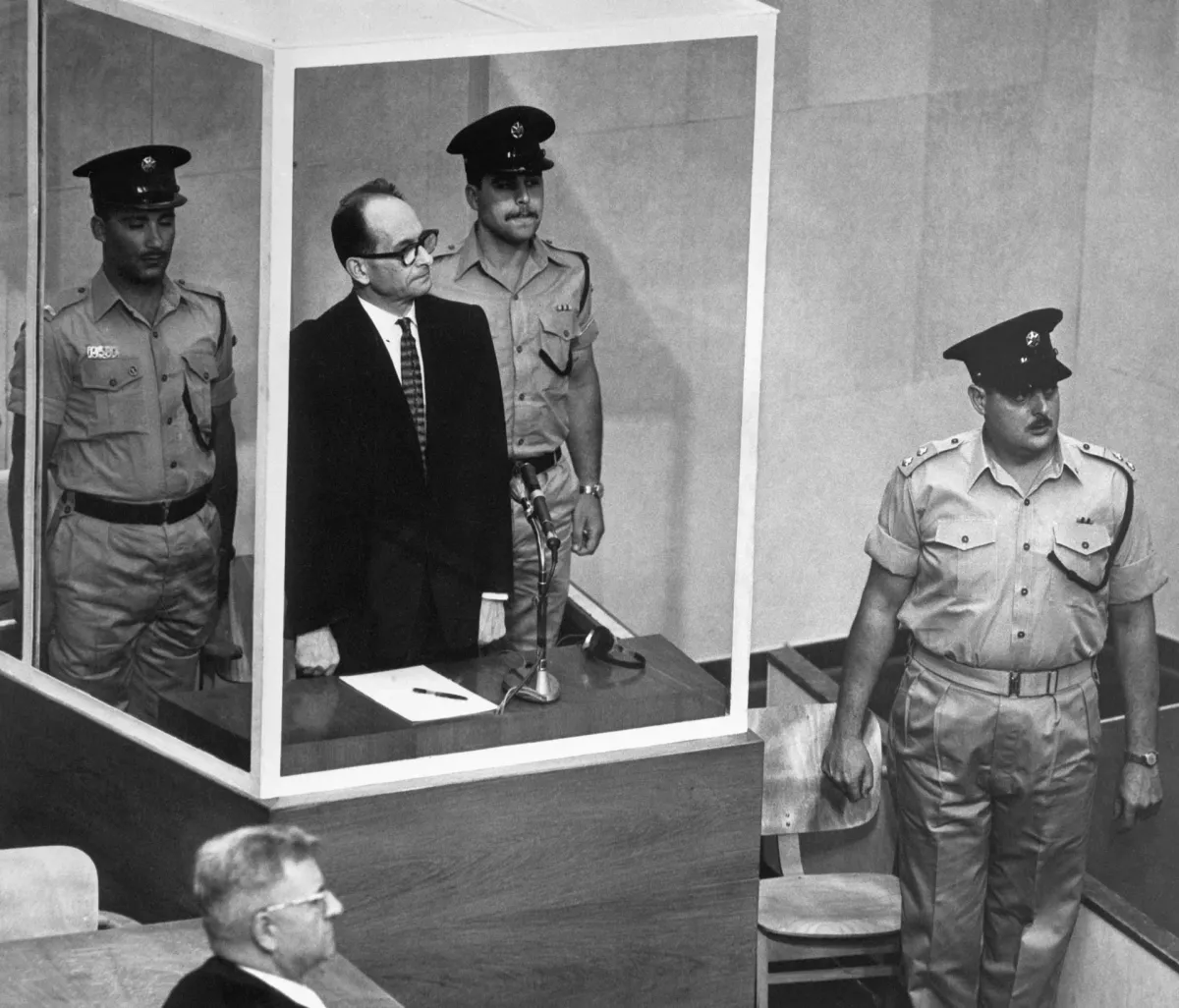

Hannah Arendt’s ‘banality of evil’, written after the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, describes how ordinary people can thoughtlessly engage in acts of evil. Whilst Arendt’s original account falters, when incorporating intention, the core account of evil is defensible.

Hannah Arendt’s ‘banality of evil’, written after the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, describes how ordinary people – for intelligible reasons – thoughtlessly engage in acts of evil. In this essay, I provide a key counterargument (and solution) to Arendt’s theory: ‘accidental evil’ – the form of which is intention as being at least necessary. Whilst Arendt’s original account falters, when incorporating intention, the core account of evil is defensible.

Importantly, only acts of the perpetrators are considered, rather than their character, since the latter is limited for discerning real-world harm (the positions of Neiman (2010) and Card (2010)). Likewise, I focus on unintentionality over intelligibility, since the latter existing is far less problematic than the former. For concise analysis, I assume along with Birmingham (2019) that, despite the Scholem letters, Arendt’s argument contains an account of radical evil.

First, Arendt (1964) describes two forms of evil as radical and banal. Radical evil is that of totalitarian regimes, which dehumanise men into “mere cogs” (1964:289). The chief effect of this is of normalising the treatment of certain humans as ‘superfluous’, and enabling ordinary people to commit terrible acts, “remot[e] from reality” (1964:288). Hence, Arendt declares an “administrative massacre” by Eichmann, arising from “the banality of evil” (1964:294). Banal evil, according to Arendt, contains two unique features: unintentionality and intelligibility; on the former, Arendt “denies that evil must be intentional” (2010:308). She argues that Eichmann simply “never realized what he was doing” – and, neither “diabolical [nor] demonic”, only “sheer thoughtlessness” motivated his crimes (1964:287-8).

Arendt anticipates an obvious counter – if banal evil is merely the normalised acts of radically evil institutions, how can individuals be held responsible? She recognises that “Eichmann was…only a ‘tiny cog’” of the wider Nazi bureaucracy – which only as a whole had the resources to produce the Holocaust. However, she refuses to relinquish Eichmann’s individual culpability: “all the cogs in the machinery, no matter how insignificant, are…transformed back into perpetrators” (1964:289). Arendt’s argument is highly convincing: Eichmann was not a cog but a man and was responsible for his active (though relatively small) participation in, and necessary support for, evil.

On the other hand, whilst largely agreeing with Arendt’s account, Neiman (2010) criticises the characterisation of Eichmann, and those like him, as ‘thoughtless’. Neiman argues that the Nazis would not “have gotten anywhere were it not for the support of millions”, and further, characterises them as either willing to walk over Jewish corpses, or as “lukewarm…bystanders who wrung their hands and retreated” (2010:310). Neiman touches on an important issue here: whilst not removing culpability, Arendt’s account diminishes the active decision, when – understanding the implications of his work for Jews – Eichmann continued ahead for a promotion. Whilst not directly intending the genocide of Jews, he nonetheless acted knowing it follow. This criticism is very convincing; if, for instance, we know that ‘fast fashion’ is an evil business, how can we wash our hands of the culpability of our conscious decision of financial support?

However, this point raises a deeper issue of Arendt’s account – of the relationship between intention and desire. Consider the case of A, who desires X yet knows that Y (a bad outcome) will also occur if he acts. Must we not admit then, by acting nonetheless, A is more than just responsible for X and Y: he intentionally does X and Y? This is compelling; though not to the same conclusion, Card (2010) also proposes evil as “reasonably foreseeable intolerable harms produced by…wrongs” (2010:16). Specifically, then, we can view intention as the decision to act, conducive to desires and accounting for effects. In the case of Eichmann, knowledge of his action’s harms was present, yet he continued, and so seems inescapably intentional (despite his desire being different).

Against this, Card also argues (further than Arendt) that intention is irrelevant for determining evil, since a theory of evil should focus on alleviating the victims’ suffering, rather than the perpetrators’ motives. However, consider the natural opposite: cases of no intention, but evil outcomes. ‘Accidental evil’, as I call it, arises from the inability to understand the effects of one’s actions. For instance, a man who – after a terrorist secretly slips a bomb into his bag – walks into an airport and causes an evil outcome. Yet, it is intuitive to us that this action is neither intentional regarding the terrorist act – as intention only exists with knowledge of the effects of action – nor evil. Whilst the outcome is clearly terrible, it seems wholly unsatisfying to label the man’s action as evil, and so too hold him responsible. Berstein (2018) makes a similar point; regarding Arendt’s accusation of banal evil of the Jewish Councils, he states that “[she] fails to take account of the wide range of behavior…some of whom committed suicide” (2018:30). Here, many Jewish Council members had prior no knowledge of their actions’ effects, and so it remains unconvincing to suggest that they acted intentionally, evilly, or that their intention has no effect on our judgement (as we should focus just on the victims).

In this way, if cases in which intention and evil outcome are present are evil – and cases of absent intention but evil outcome are not evil – then intention must be at least necessary for the classification of evil. Whilst contrasting with Arendt’s initial claim that evil need not be intentional, it seems that the general form of banal evil – of ordinary people committing evil without a direct desire for it – is maintained when adopting intention as a necessary condition. This solution is the most convincing, since we account for ‘accidental evil’, whilst acknowledging the banality of Eichmann’s evil crimes.

In conclusion, whilst Arendt’s theory is largely convincing, a stronger account is needed to interrogate the implications of choosing to act despite knowledge of effects. If applied to all outcomes that are known beforehand, then intention is clearly a necessary condition for evil acts. I note that this inclusion does nothing to Arendt’s previous definitions of banal, radical, or perhaps even ‘diabolical’ evil; Eichmann still commits evil if he has knowledge of the implications of his act, even if this is more banal than Hitler – who commits evil with more direct intent (as his desires and primary effects of the act are aligned).

Whilst there is much more nuance to the arguments than I have placed here – such as the difference between ‘motivations’, ‘desires’, ‘judgements’, and ‘intentions – the adjustment I have suggested to Arendt’s ‘banality of evil’ in its general form allows it to be defensible against contemporary criticism.

Bibliography:

- Arendt, H. (1964), “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil”. Penguin Books (5th ed.), 1994.

- Bernstein, R. J. (2018), “Why read Hannah Arendt now?”. Polity Press, pp. 30-33.

- Birmingham, P. (2019), “Hannah Arendt’s Double Account of Evil: Political Superfluousness and Moral Thoughtlessness”, in “Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Evil”, Nys, T. and de Wijze, S. Routledge, pp. 148-162.

- Card, C. (2010), “Confronting Evils: Terrorism, Torture, Genocide”. Cambridge University Press.

- Neiman, S. (2010), “Banality Reconsidered”, in “Politics in Dark Times: Encounters with Hannah Arendt”, Benhabib, S. Cambridge University Press, pp. 305-315.