The 1995 and 2004 EU Enlargements: A warning for Ukraine?

The 4th and 5th enlargements of the European Union have had wide-ranging effects on its identity and policy, yet there is still much debate over the extent these changes in comparison.

The 4th and 5th enlargements of the European Union have had wide-ranging effects on its identity and policy, yet there is still much debate over the extent these changes in comparison. This essay discusses the two enlargements, and how they have affected the construction of EU actorness – in particular, the capacity and cohesiveness of the EU regarding economic and foreign policy goals.

With Ukraine (alongside Georgia and Moldova) seeking a fast-track to EU membership, the Ukraine war may indeed be tipping the continent into a new wave of enlargement. In this case, it is vital to understand the differing cases of 1995 and 2004 to understand the possible impacts future enlargements may have on EU actorness in a range of areas.

When considering the relative effects of both enlargements, the 1995 enlargement enhanced EU actorness in terms of capacity and cohesion, for both economic and foreign policy. However, the 2004 enlargement undermined economic capacity and cohesion – and foreign policy cohesion – though cohesion clearly has an underlying problem with the status of the CSDP. In this way, both enlargements impacted EU economic actorness, but – whilst opposite in effect – are unlikely to have had a significant effect on EU foreign policy actorness.

Introduction:

The European Union (EU) has undergone seven enlargements since its inception in 1951. However, the 4th and 5thenlargements in 1995 and 2004 respectively can be seen as key turning points for the identity and overall actorness of EU institutions and policies. Both similarly involved the expansion of the EU into new areas of Europe, first into the north, and later into the post-communist East. Yet, there remains significant differences in both the nature and extent of these enlargements, and their effects on the EU generally. This essay seeks to ameliorate these differences and provide an analysis of the ways in which they changed EU actorness in the areas of foreign and economic policy.

The essay begins with a historical prelude to the EU policy of enlargement, and the ideological motivations behind it. This is to understand the aims of EU actorness regarding the pursuit of enlargement. The 1995 and 2004 enlargements are explained in detail separately, before an analysis on the comparative effects on EU actorness (in the aforementioned policy areas). Concluding remarks are then given, as well as the potential relevance to contemporary enlargement candidates such as Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia.

To assess the effect of both enlargements on EU actorness, the main policy areas of foreign policy and economics are discussed. Whilst other areas – such as environmental or normative policy – were affected by these changes, for the sake of a concise and coherent analysis, only these main policy areas are discussed.

On the other hand, to maintain a clear analysis, the notion of actorness is assumed to refer to the capacity and cohesiveness of the EU on policy. This is taken from Ekengren and Engelbrekt (2006), in contrast to other conceptions, such as the ‘capability-expectations gap’ utilised in earlier works by Hill (1993). This is to account for the greater fragmentation of ‘expectations’ that exist in the post-2004 enlargement period. Whilst more advanced conceptualisations of actorness are available – as outlined empirically by TRIGGER (2019) – these lie outside the scope of this essay. Thus, the effects of both enlargements are considered in their impact on the capacity and cohesiveness of the referenced EU policy areas, within such a combined framework.

1. Historical context of EU Enlargements

In order to understand the 1995 and 2004 enlargements, it is useful to first understand the historical context, and by extension, the motivation behind the pursuit of a larger membership.

Initially an economic community under the Schuman Plan of 1950, European members sought a form of integration which would be mutually beneficial for the reconstruction of Western Europe post-WWII, but also more broadly, help create a ‘European identity’, making future wars both unthinkable and materially impossible. Thus, from its inception – as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) – the EU was focused on both a common economic and normative identity for its member states. The (failed) European Defence Community (EDC) proposals just two years later also underlined a desire to include a similarly common foreign policy to the union.

However, Hill, Smith, and Vanhoonacker (2017) notes that at this time, the ECSC was not able to create a federal system akin to that which we see today – in fact, Franco-German tensions endured up until the start of the 1990s (and arguably continued in the rise of illiberal democracies in Europe after this, although to a lesser extent). Unsurprisingly, then, as time passed, the community continued to integrate further with more common policies – such as proposals for a Customs Union and Common Agricultural Policy in 1955 – but remained largely inwards-looking. It was not until 1969, as Bindi (2012) notes, with Pompidou’s Triptique, that the notion of enlargement would be suggested. Pompidou’s vision for the future of Europe consistent in the three principles of completion, deepening, and enlargement – the final of which would be implemented in 9173, with the 1st wave of enlargement, bringing Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom into membership.

Here, the understanding of the European project began to subtly change. Whereas before the focus was in deepening the ties of antagonistic Western-European states, EU began to see itself as having the potential to become a major power on the world stage – able to promote its values and stability across the continent. As such, enlargement increasingly became seen as a key part of pursuing this vision; by bringing in more states, the EU would be able to shape them in accordance with their norms and values, whilst strengthening the economic prosperity and international influence of the EU as a whole.

These principles were strengthened with the signing of the Single European Act (SEA) in 1986, and later the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. Both these vastly increased the normative and institutional integration within the EU and implemented far stronger scope and powers for the supranational organisation, such as preparations for a common currency (the Euro) and the creation of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Furthermore, Bindi (2012) notes that between November 1993 and May 1995, eight joint actions – ranging from promoting peace in Central- and Eastern-European countries, providing humanitarian aid to Bosnia, and promoting the indefinite extension of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – were pursued. All of this sought to strengthen the integration (economically and normatively) between member states and expand the EU’s influence across the world. It is no surprise then, that – for the motivations explained previously – the EU saw a rapid series of enlargements in this period, in 1981, 1986, and eventually 1995. Much of the motivation behind increasing enlargement, then, can be seen as an extension of the changing vision for the EU, towards a global power able to spread normative influence, and secure peace and prosperity across an integrated Europe.

a. The 1995 Enlargement

The 4th wave of enlargement pursued by the EU involved adding key Northern-European nations to membership: Finland, Sweden, and Austria. On the EU side, the enlargement was a largely a response to the failure in both the 1980s with regards to the Soviet Union, and in the 1990s with regards to Yugoslavia, of EU foreign policy. In particular, the 1991 war in Yugoslavia, according to Bindi (2012), highlighted the weakness of the EU’s fragmented foreign policy; the EU’s futile negotiations in the first year was only saved once the United States aided in negotiations, ending with the 1995 Dayton Accords. Harking back to the foundations of the European project – in part to prevent the horrors of genocide in Europe – the Bosnian genocide in particular raised serious questions about the EU’s responsibility towards human rights and the need for a common foreign policy. Enlargement into Northern Europe was seen as a key step to ensuring the greater security on the continent.

On the candidate side, the motivations were similar. Each of the states were developed almost in line with levels of other member states, and in fact, were initially hesitant to join, on account of jeopardising their own system of economic organisation: the so-called ‘Nordic model’ (seen as incongruent with the free-market deregulation of the European Economic Community (EEC)). Whilst Nordic countries engaged with the EEC via the European Free Trade Area (EFTA), importance on was placed on national sovereignty, and their continued neutrality – particularly given proximity to Soviet Russia.

According to a study by the European Parliament Research Service (EPRS) (2015), two key developments changed this. First, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 gave candidates a chance to redefine neutrality, freeing up the possibility of closer relations with the EEC. Second, under the backdrop of economic crises, Nordic countries feared losing access to markets as proposals of a Single Economic Area in Europe gained prominence. By 1995, the candidates had made their decision.

b. The 2004 Enlargement

The next wave of enlargement came in 2004, with the accession of: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The enlargement encompassed most of the former-Soviet states, found across Eastern Europe. Given the previous discussion, the EU interest in enlargement into Eastern Europe should be unsurprising; the 5th enlargement held the promise of a far greater influence as a normative and global power, spanning almost the entire of continental Europe. Movement towards the 5th enlargement was clear from 1989-91, where Hill, Smith, and Vanhoonacker (2017) highlight the heavy EU involvement in programmes assisting former Soviet states. As we shall see then, even the act itself of enlargement, can be seen as a practice of EU actorness.

However, the 2004 enlargement also – similar to 1995, but more directly – was pursued as a response to the war in Yugoslavia, as well as the 1999 Kosovo crisis. As Bindi (2012, p. 31) explains, enlargement into the east gave the EU closer leverage over the troublesome Western Balkans and allowed a further “accession strategy” to develop. On the candidate side, Lammers (2004) notes that joining the EU was most obviously motivated by the economic difficulties many faced, with small economies, largely made dependent after decades of Soviet control. Additionally, many sought the implied security of a supranational organisation, now left to fend for themselves.

The 5th wave is by far the largest enlargement the EU has embarked upon. It has also been criticised – despite the rigorous tests of the ‘Copenhagen criteria’ – as allowing for the internalisation of the states most different to existing member states. Candidates varied vastly in terms of language, history, economic and political structure, among others. This said, as explained by EUR-Lex (2007), though initial negotiations began in 1990, the principle of ‘differentiation’ meant that the pace of progress was adapted to each candidate, based on their preparedness.

2. Comparative study of the Effects of Enlargements, in relation to EU Actorness

Having understood the reasoning and nature of both enlargements, it is now necessary to evaluate the effect of these enlargements on EU actorness – where actorness pertains to both the cohesion and capacity of the EU to enact its common policies. As Ekengren and Engelbrekt (2006) explain, capacity refers to the specific resources the EU is able to mobilise in aid of its policies, whilst cohesion is contingent on a significant degree of similarity in perception of values, identities, interests, or threats.

a. Effect on Economic Policy

First then, as initially an economic community, EU actorness regarding economic policy is of particular importance. This refers both to the EU’s ability to exercise control over areas such as agricultural policy, monetary policy, and labour policy, but also the general economic integration of member states.

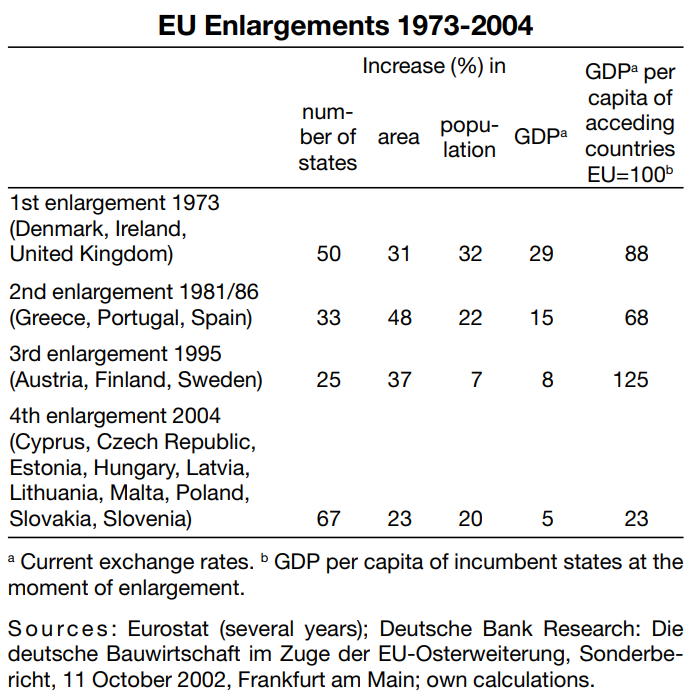

Unsurprisingly, the effect on EU actorness from the 1995 enlargement was relatively small. In his detailed economic research, Lammers (2004) compares the various enlargements in terms of their macroeconomic significance. Whilst Finland, Austria, and Sweden were relatively small economies, they were well-developed and had labour laws and monetary policy already largely in line with the European standard. The enlargement only led to a 7% increase in population and retained a healthy GDP per capital at aggregate of 125. Therefore, the impact on capacity of these two areas of economic policy as a result of the 1995 enlargement was relatively small, aided by the small number of states and similar political perspective of these states, allowing also for a continuation of cohesion.

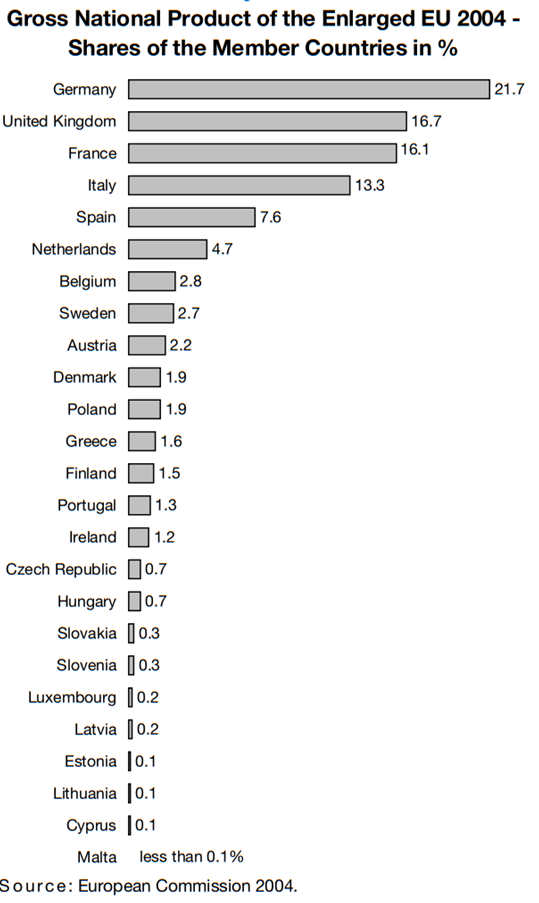

By contrast, the effect of the 2004 enlargement was far more dramatic. Again, Lammers (2004, p. 132) notes that “no previous enlargement has admitted new countries so different in economic terms from the existing EU members”. As seen in Figure 1, the enlargement involved a 20% increase in population – most of which were drawn from states with sparsely-populated, rural economies – and held a dwindling GDP per capita on aggregate of just 23. As post-Soviet states, the new member states had stunted economic growth, and remained now the poorest of the EU.

To make matters worse, these states were poorly adjusted to the liberal economic models of the EU, requiring a significant adjustment process to integrate. This included institutional changes in the form of a removal of all tariffs to join the Customs Union, implementation of the ‘four freedoms’ (free movement of goods, services, capital, and people) to join the Internal Market, and the ceding of certain economic powers to join the EU Budget. These economic facts led to significant challenges for the capacity and cohesion of the EU to pursue economic policy, since adjustment took many years to complete, and even then, the new states remain very small parts of the EU’s economic capacity (despite receiving large portions of redistribution). As Lammers (2004, p. 132) notes, the difference between new and old member state economies would have challenging effects on cohesion as well: “the low cost of labour in these countries will…place competitive pressure on the economies of the old member states”. The influx of low-skilled labourers – particularly from Poland – into existing member states would prove challenging for cohesion, especially in members like the United Kingdom, whose 2016 Brexit campaign based much of their misgivings on low-wage migrant workers. Whilst Lammers (2004) demonstrates that the potential future growth rate of the 10 new members may later solve these challenges, these gains in many states have yet to be realised. As such, it is undeniable that the 2004 enlargement has to a large extent undermined both the capacity and cohesion of EU economic actorness.

b. Effect on Foreign Policy

Secondly, as we have seen, part of the act of enlargements has been an attempt to secure greater stability on the continent – and thus, is itself an act of EU foreign policy actorness. But the issue over to what extent each enlargement has undermined this actorness remains.

As previously explained, the 1995 enlargement was largely an attempt to secure greater security in the wake of the war in Yugoslavia, as well as extend influence further into Northern Europe. By bringing in Austria, Sweden, and Finland, the EU now for the first time shared a border directly with Russia. As Ekengren and Engelbrekt (2006) note, not only did this strengthened the EU’s leverage for matters of security, but it also helped renew a focus on crisis management and conflict prevention in the CFSP. Specifically, the 4th enlargement led to the Petersberg Tasks, and a refocusing of the EU agenda from defence to conflict management. In fact, most of the defence forces that were present in the Baltic region, were built up by these new Nordic members. Thus, the 1995 enlargement was instrumental in increasing the cohesiveness and focus of EU foreign policy actorness.

By contrast, the 2004 enlargement seemed to have the opposite impact. Ekengren and Engelbrekt (2006, p. 21) explain that “the diversity of the individual countries has never been more overwhelming”; the differences both between existing and candidate member states, as well as between candidates, were vast. What can Poland and Malta, or Estonia and Cyprus, be said to have in common with each other, aside from their EU membership? To make matters worse, in the process of enlarging, the EU gained the complex heritages and unique perspectives of each member; to Russia and Ukraine through the accession of the three Baltic states and Poland, and to Turkey from Cyprus. The conviction of these positions would undermine the cohesiveness of the EU and put it in a headlock when attempting to confront these issues (such as Turkish membership of the EU, or the Ukraine War).

This said, whilst the 2004 enlargement certainly damaged the EU’s external policy actorness, it is difficult to see how dramatic a change this was, given the already fragmented and vague position it found itself in. In particular, the EU lacked a cohesive external policy vision; as Hill, Smith, and Vanhoonacker (2017, p. 16) writes, it is “far from clear that the EU has a unified or consistent view of the model of world order it would wish to bring about”. This comes despite the adoption of the European Security Strategy (ESS) in 2003. Risse (2012) explains that the majority of the lack of cohesiveness was not found from new member states, but the oldest: splits over the 2003 Iraq war, for instance, saw divisions between the UK and Spain on one side, and France and Germany on the other, among others. This was seen once again over the issue of Libyan intervention in 2011, and the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict. These divisions lie much deeper in the heart of the European project, and so is difficult to lie at the feet of the 2004 enlargement specifically.

These divisions have continued past the 6th and 7thenlargements, seen in the fragmented response and varied positions in response to both the 2015 Migration crisis and 2022 Ukraine war. This failure has led to many member states taking external policy into their own hands, as Hill, Smith, and Vanhoonacker (2017, p. 5) again argues:

“The EU’s comparative weakness in dealing with geopolitical questions has been exposed…In these circumstances the bigger member states have fallen back on their own resources”.

Risse (2012) puts this issue down to the refusal of the oldest of the member states to supranationalise the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), which accounts for the inability of the EU to speak with one voice on matters of foreign policy. Established in 1997 by the Treaty of Amsterdam, the CSDP provides the EU with the means to conduct crisis management operations across the world and encompasses a range of civilian and military instruments. Unsurprisingly, the CSDP was established as a means of supplementing the similar work of the United Nations and NATO, in promoting peace and security internationally.

However, the CSDP remains an intergovernmental policy, meaning that the final decisions are ultimately made by the member states themselves (despite the coordinating role of the EU). Without supranationalisation, Risse (2012) correctly argues that important member states are able to independently pursue their own foreign policy agenda, leading to the current fragmentation of EU external policy we see today. Risse (2012) attributes this refusal to a wider problem of a European identity crisis, but this lies outside the scope of this essay.

As such, whilst we observe damaging effects of the 2004 enlargement on EU foreign policy actorness, much of these can also be convincingly attributed to the larger issue of the status of the CSDP among member states. In this way, whilst the division is somewhat unclear, evidence suggests that the majority of the blame lies to the older member states, rather than the 5th enlargement.

Conclusion:

In conclusion then, we have seen the historical basis for enlargement more generally, since the inception of the European project in the 1950s. As far back as Pompidou’s Triptique a general vision of the EU as a global economic and normative power emerged, which was to be supported by further enlargement of the supranational body’s borders. These goals were strongly represented in both the 4th and 5thenlargements, with the expansion into Northern Europe partially a response to gain closer economic relations with the Nordic model economies and gain greater normative legitimacy after democratic deficits identified by the European Parliament after the Maastricht Treaty. In much the same way, the 2004 expansion remained another example of EU economic and foreign policy actorness, as an attempt to reunify continental Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union, and to pursue greater foreign policy influence in the wake of the wars in Yugoslavia and Kosovo.

Whilst both enlargements themselves can be seen as examples of the EU’s foreign policy and economic actorness, it is also clear, however, that they themselves changed the capacity and/or cohesiveness of the EU as a whole. The 1995 enlargement, as we have seen, had a positive impact on both the foreign policy and economic capacity of the EU, even if somewhat limited in economic terms by the size of their economies, and number involved in enlargement. By contrast, the 2004 enlargement had clearly negative effects on the capacity of economic actorness – requiring significant adjustment and redistribution, whilst contributing little economically in return.

Furthermore, issues relating to the migration of cheap labour from these new members presented a significant challenge to the cohesion of wealthier member states, particularly the UK. With new candidates of Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia sharing many similarities with the 10 admitted in 2004, it is likely to spur similar challenges if the EU enlarges again. After the Black Sea grain agreement, signs of what may come were observed in cheap Ukrainian grain flooding Polish markets and pushing out many domestic farmers. This explains to some extent the phenomenon of ‘enlargement fatigue’ experienced by many members, who are exhausted by the continued challenges and loss of cohesion associated with diverse enlargement.

Finally, given the geographical similarity of Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia to the 2004 enlargement candidates – and their similar complex entanglements, particularly with Russia – it is likely that much of the effects to EU foreign policy cohesion from 2004 would be repeated. Whilst it is difficult to measure the effect of 2004, clearly there was somewhat of a negative effect, which would likely be worsened if a similar enlargement involving these countries was pursued (without counter-steps, e.g. supranationalisation of the CSDP).

Bibliography:

- Bindi, F. (2012) “European Union Foreign Policy: A Historical Overview”, in Angelescu, I. and Bindi, F. (ed.) “EU Foreign Policy Tools”, 2nd ed., Brookings Institution Press.

- Ekengren, M. and Engelbrekt, K. (2006) “The Impact of Enlargement on EU Actorness: Enhanced capacity, weakened cohesiveness”, in Hallenberg, J. and Karlsson, H. (ed.) “Changing Transatlantic Security Relations: Do the U.S, the EU and Russia Form a New Strategic Triangle?”, 1sted., Routledge.

- EUR-Lex (2007) “The 2004 enlargement: the challenge of a 25-member EU”, eur-lex.europa.eu, Date Accessed: 06/05/2023. Link: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/the-2004-enlargement-the-challenge-of-a-25-member-eu.html

- European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) (2015) “The 1995 enlargement of the European Union: The accession of Finland and Sweden”, European Union History Series, Historical Archives Unit.

- Hill, C. (1993) “The Capability-Expectations Gap, or Conceptualising Europe’s International Role”, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 31, No. 3, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 305–28.

- Hill, C., Smith, M., and Vanhoonacker, S. (2017) “International relations and the European Union”, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press.

- Lammers, K. (2004) “How Will the Enlargement Affect the Old Members of the European Union?”, Intereconomics, Vol. 39, No. 3, Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Risse, T. (2012) “Identity Matters: Exploring the Ambivalence of EU Foreign Policy”, Global Policy, Vol. 3, No. 1, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Trends in Global Governance and Europe’s Role (TRIGGER) (2019) “The TRIGGER Model for Evaluating Actorness: Testing EU actorness and influence in domestic and global governance”, European Union Horizon 2020 project.